Character-Setting-Character Triangles: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<div class="meta"> | <div class="meta"> | ||

This text and art is | This text and art is derived from work originally in ''[[system::Fourth World]]'', and is released here under the the [https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International license]. | ||

Icons by [http://lorcblog.blogspot.com Lorc] and [https://delapouite.com Delapouite] from [https://game-icons.net game-icons.net] ([https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ CC BY 3.0]) | |||

</div> | |||

Many role-playing games expend no effort to link the player characters together during [https://slyflourish.com/running_session_zeros.html session zero]. (Some games don't even have a session zero.) This misses a big opportunity to arm the players with tools that can help a campaign start strong. | |||

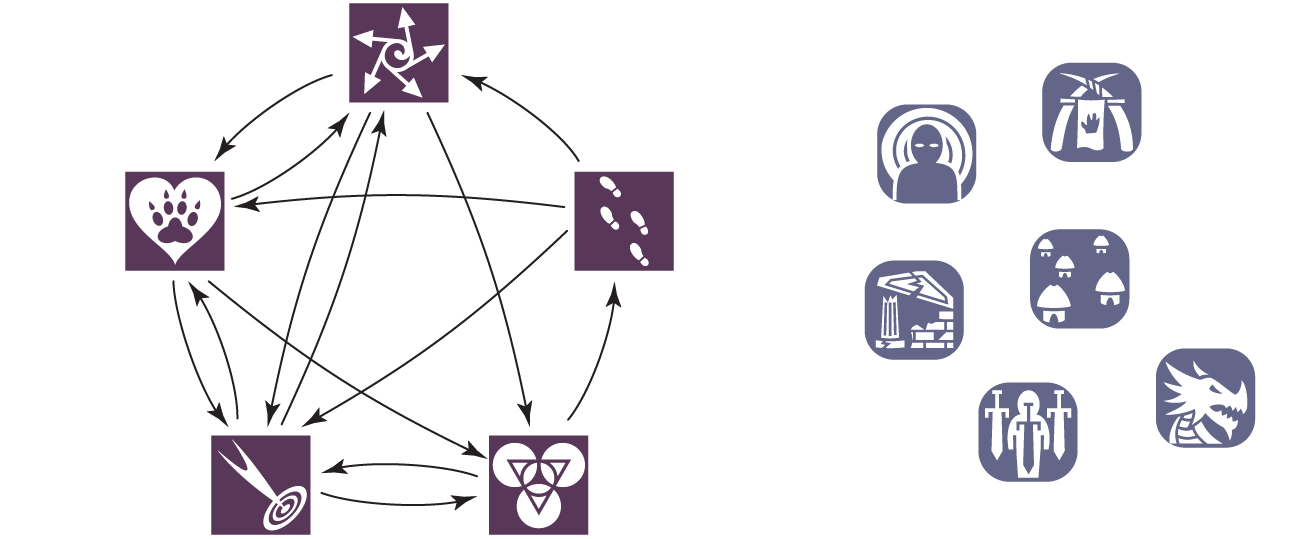

Still other games have procedures that point the PCs at each other (''Dungeon World'' has [https://www.dungeonworldsrd.com/character-creation/#12_Choose_Bonds bonds], for example). While these are helpful, they also miss an opportunity, because they are insular. They only connect to the characters to each other. When completed, while you had a nicely tangled web of character connections on one hand, you also had a bunch of setting just sitting off by itself, like this (each PC is a purple square, setting elements are blue squares with rounded corners): | |||

<div class="extimg"> | |||

https://rpg.divnull.com/graphics/bonds-closed.png | |||

</div> | |||

== Useful trigonometry == | |||

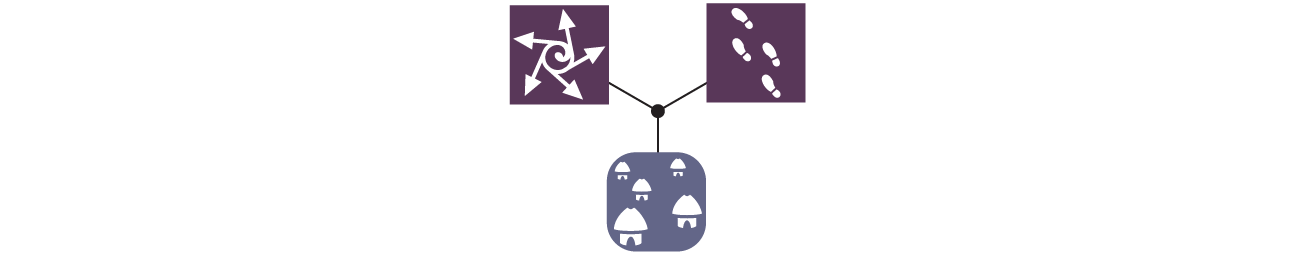

Instead, create '''PC-setting-PC triangles''', where two player characters share a relationship with a person, place or thing in your setting. For example, suppose the elementalist and the scout got banished from the same village: | |||

<div class="extimg"> | |||

https://rpg.divnull.com/graphics/bonds-triangle.png | |||

</div> | |||

The two PCs are now connected not only to each other, but also to the setting, and in a way that the players now know about that piece of the setting, and have some idea about their characters' opinion of it. This works even when the connection isn't strong. For example, perhaps the two weren't banished at the same time, or for the same reason, and have never even met. Their common experience still creates useful hooks for play. | |||

You can build these triangles by asking '''bonding questions''', which establish connections between PCs, but then digging in a bit more to try to tie their answer to the setting in some way. Try to give different pairings different parts of the setting to chew on. To introduce setting elements to the players, you can just lay some post-its or index cards or something that just have the name, or short description, of the elements (e.g. “a ruined temple”, “a tribal leader”). You don’t need to dump a book of lore on anyone, or even describe them. They don't even need to have been fully defined. Often what the players assume about them is more useful for building out an idea. | |||

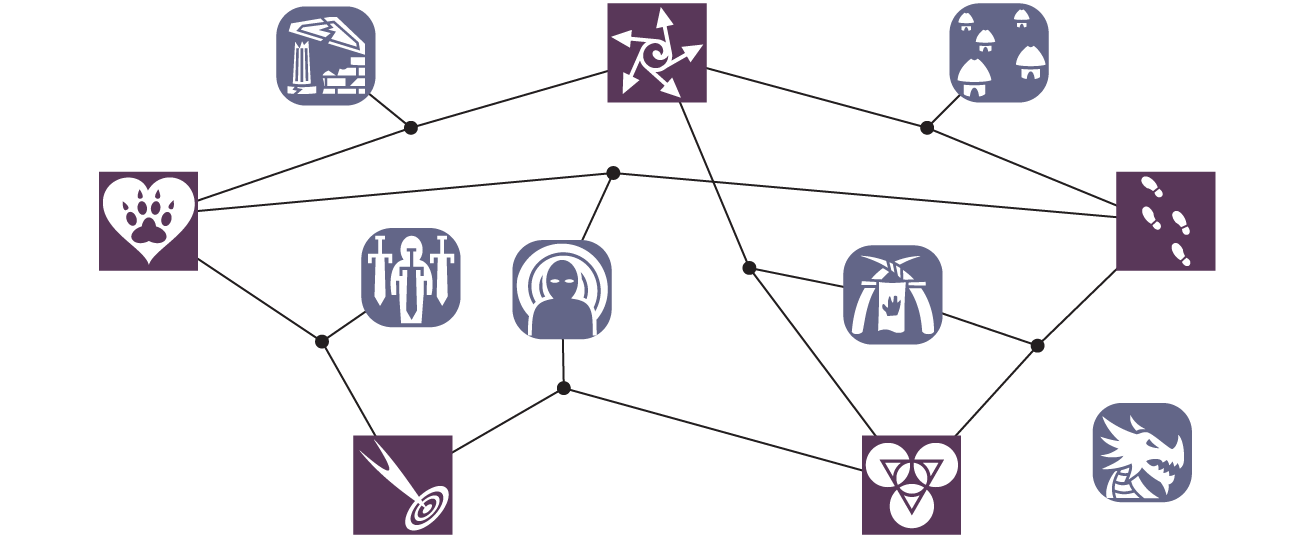

In the end, you’ll have a web of interactions that will often suggest play: | |||

<div class="extimg"> | |||

https://rpg.divnull.com/graphics/bonds-open.png | |||

</div> | </div> | ||

[[ | == Plurium interrogationum == | ||

A powerful technique for using questions to define character background, connect the party members, and, especially, create triangles with the setting, is ''plurium interrogationum'' (literally “of many questions”): a type of question containing a supposition that must be assumed to be true to even answer the question. This technique is better known for creating [https://www.thoughtco.com/complex-question-fallacy-1689890 logical fallacies], but it can be used for good when trying to flesh out a character. When creating characters or starting an adventure, the supposition is often something that has never been mentioned before, but is considered true thereafter. | |||

For example, consider a question like: “when your brother went off to fight in the war, how did it affect your family?” There are several suppositions here, none of which might have ever been established before: | |||

* A war is either in progress or happened recently. | |||

* The character being asked the question has a brother. | |||

* Something about the brother leaving to fight traumatized those left behind. | |||

The player’s answer will likely tell everyone something interesting about the character’s relation to her family, but just asking the question has illuminated the setting, and connected at least one character to it. The player might also just reject the premise of the question the GM offers up (“I don't have a brother!”), but that, too, tells everyone something about where the player wants to go, particularly with follow up questions. | |||

By asking this sort of question, the GM is simultaneously injecting what they know about the setting and introducing it to the players (e.g. the war in the example above). | |||

In a [https://www.gauntlet-rpg.com/blog/establishing-questions blog post], Jason Cordova calls these '''establishing questions''', and suggests two different ways of using them. The first is more general, targeted at characters with particular disciplines or species. These tend to work best when creating characters right before play. The second are tailored to individual characters, and usually require a bit of thought or knowledge about the particular character. | |||

Establishing questions excel at building PC-setting-PC triangles, or just connections of a single character to something setting specific. Even after character creation, they can be a useful way to jump start some new element of a the game, such as when starting a new adventure or entering a new steading. | |||

Questions like this can also foreshadow events, or give the players hints and nudges about what they may soon face. They are also a great way to give a character knowledge that the other characters may not know, but all their players do. | |||

While most useful at the table, examples of this style of question are difficult to provide here, as they work best when supposing specific elements of whatever setting/adventure the characters will next encounter. | |||

Latest revision as of 13:46, 11 November 2024

Many role-playing games expend no effort to link the player characters together during session zero. (Some games don't even have a session zero.) This misses a big opportunity to arm the players with tools that can help a campaign start strong.

Still other games have procedures that point the PCs at each other (Dungeon World has bonds, for example). While these are helpful, they also miss an opportunity, because they are insular. They only connect to the characters to each other. When completed, while you had a nicely tangled web of character connections on one hand, you also had a bunch of setting just sitting off by itself, like this (each PC is a purple square, setting elements are blue squares with rounded corners):

Useful trigonometry

Instead, create PC-setting-PC triangles, where two player characters share a relationship with a person, place or thing in your setting. For example, suppose the elementalist and the scout got banished from the same village:

The two PCs are now connected not only to each other, but also to the setting, and in a way that the players now know about that piece of the setting, and have some idea about their characters' opinion of it. This works even when the connection isn't strong. For example, perhaps the two weren't banished at the same time, or for the same reason, and have never even met. Their common experience still creates useful hooks for play.

You can build these triangles by asking bonding questions, which establish connections between PCs, but then digging in a bit more to try to tie their answer to the setting in some way. Try to give different pairings different parts of the setting to chew on. To introduce setting elements to the players, you can just lay some post-its or index cards or something that just have the name, or short description, of the elements (e.g. “a ruined temple”, “a tribal leader”). You don’t need to dump a book of lore on anyone, or even describe them. They don't even need to have been fully defined. Often what the players assume about them is more useful for building out an idea.

In the end, you’ll have a web of interactions that will often suggest play:

Plurium interrogationum

A powerful technique for using questions to define character background, connect the party members, and, especially, create triangles with the setting, is plurium interrogationum (literally “of many questions”): a type of question containing a supposition that must be assumed to be true to even answer the question. This technique is better known for creating logical fallacies, but it can be used for good when trying to flesh out a character. When creating characters or starting an adventure, the supposition is often something that has never been mentioned before, but is considered true thereafter.

For example, consider a question like: “when your brother went off to fight in the war, how did it affect your family?” There are several suppositions here, none of which might have ever been established before:

- A war is either in progress or happened recently.

- The character being asked the question has a brother.

- Something about the brother leaving to fight traumatized those left behind.

The player’s answer will likely tell everyone something interesting about the character’s relation to her family, but just asking the question has illuminated the setting, and connected at least one character to it. The player might also just reject the premise of the question the GM offers up (“I don't have a brother!”), but that, too, tells everyone something about where the player wants to go, particularly with follow up questions.

By asking this sort of question, the GM is simultaneously injecting what they know about the setting and introducing it to the players (e.g. the war in the example above).

In a blog post, Jason Cordova calls these establishing questions, and suggests two different ways of using them. The first is more general, targeted at characters with particular disciplines or species. These tend to work best when creating characters right before play. The second are tailored to individual characters, and usually require a bit of thought or knowledge about the particular character.

Establishing questions excel at building PC-setting-PC triangles, or just connections of a single character to something setting specific. Even after character creation, they can be a useful way to jump start some new element of a the game, such as when starting a new adventure or entering a new steading.

Questions like this can also foreshadow events, or give the players hints and nudges about what they may soon face. They are also a great way to give a character knowledge that the other characters may not know, but all their players do. While most useful at the table, examples of this style of question are difficult to provide here, as they work best when supposing specific elements of whatever setting/adventure the characters will next encounter.